Friday, December 14, 2012

traumatic grief

The death of a child is never easy because whether or not it is expected, it runs counter to the expectations of our support systems. Parents are supposed to die before their children. And we mentally and socially prepare for the deaths of our loved ones as they age. We don't typically prepare for the deaths of children unless that situation arises, and our social networks aren't typically set up to support grieving for children.

The loss of a child becomes much harder to bear when the death is unexpected and/or violent. Elizabeth Kubler-Ross articulated a theory of stages of grief in relation to loss in her 1969 classic On Death and Dying. A person is supposed to move in time through denial, anger, bargaining, despair/depression, and eventually to acceptance. This process can become arrested in the face of an overwhelming loss due to traumatic circumstances such as today's. When someone is intimately affected by such a shock and loss, their nervous system goes into survival mode curtailing the process of healthy grieving in order to get through immediate events.

I hope that those most directly affected are able to connect with mental health services and disaster response. I have quite a bit of confidence in EMDR's Recent Traumatic Events Protocol as well as the effects of treating traumatized children with Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy including its supplement for traumatic grief.

It is terror to imagine children being killed and witnessing killing. Other than organizing for direct response in order to provide appropriate mental health services to the survivors and families, I think one of the best responses is to offer metta--real loving-kindness. May they be safe; may they be happy; may they be strong; may they live with ease.

I was an elementary school teacher for DC Public schools during the DC sniper's reign of terror. Someone called in a suspicious person on a nearby roof, which led to several 4th grader's puppy piled in a corner with me, while I anxiously read them stories for almost two hours while waiting for the "all-clear".

No one among us has not experienced overwhelming fear. Likewise most of us have experienced moments of overwhelming anger and confusion. Whether the killer was suffering from the type of extreme alienation (first described in modern psychological terms by Karen Horney) or acute mental illness (Melanie Klein's schizoid position), he was having a hellish human experience that led to the murder of children. The easiest way to widen the gap between our own state of mind and the mindstates that lead to violence is to practice kindness and clarity.

Start easy and direct your love towards the surviving children. They need it. May they feel safe. Give it also to family members of survivors and victims. May they feel strong. Add others as you can. The first responders: May they feel content and strong. The police and public officials: May they live with ease.

The perpetrator will probably be harder. Keep in mind that he once was a little baby to his caretakers. At some point along the way he became oppressed by mindstates that led to a combined lack of clarity and kindness so sever that he could take the lives of children. And whatever the circumstances, he did what he did in order to attain something that would put him more at ease. May he be released from affliction.

If you're not there yet, don't sweat it. Give yourself some metta. May I feel safe; may I feel happy; may I feel strong; may I live with ease.

Wednesday, June 20, 2012

Metta in the Spirit of Zen

Metta as a practice is radical: it is radical in its openness; it is radical in its clarity; and it is radical in its scope. (links jump down)

When we practice metta as a formal practice daily, we bring to the practice our state of mind however it appears in that moment that we sit down and then moment after moment afterwards. Whether or not we feel open in any given moment, it is a practice of opening up. We practice dropping our agenda and conventional thoughts towards the object of metta (whomever we have chosen to be the recipient). Whether the person has slighted us or nurtured us or both, we direct our kindness and openness to them. And whether we are practicing by chanting Kwanseum Bosal, or by reciting Om Mani Peme Hung, or by repeating phrases such as "May he feel safe", etc., we direct as much kindness as we can without getting caught by thoughts about the relationship.

Dipa Ma- the great meditation master of the late 20th century was known to say on several occasions to say that metta practice and vipassana were not different. The latter refines attention and directs it at certain phenomena until it becomes perfectly clear that while the car may be turning this way and that way, there's no one at the wheel. As a correlate, the deep realization of not-self necessitates an appreciation for how a feeling of self is created from moment to moment as an attempt to use an agenda to get comfortable.

In metta practice, the order is a bit reversed. We practice dropping the agenda as we direct metta towards whomever, and as we feel resistence to doing so, our agendas become crystal clear. This is not a grueling practice, when done mindfully. Metta itself creates a feeling of mental space in which things can arise clearly. And in that clarity, all the ways we resist what is happening in the moment become very clear. This is a very different state of affairs than how someone might imagine filling the mind with love. And while blissful states of samadhi can arise from this practice, my experience of this practice is that it creates a sort of reflexive equanimity. May you be well, and you, and you, and you. No exceptions. And when that equanimity doesn't arise, it's like putting a big neon sign on whatever is causing resistance. It can be uncomfortable, but that's really the fruit of practice- to be able to give attention to what requires it. Clarity is a boon.

A scary realization can ocurr when a practitioner just begins to really give himself or herself over to the formal practice of metta. I experienced it as a child might feel when he has to apologize to someone and admit that he was wrong. In this case what was brought to the surface for me was the recognition that I have nothing to lose by others being happy. For years I thought I knew that to be true and believed it. I didn't think I was a phony. I mean, I had over the course of many years of practice gotten into the habit of wishing others well, wishing for freedom from whatever binds them. I'm not suggesting that my previous years of practice and its effects were only skin deep, so much as I realized that they were conditional. Finicky, even! Metta brought home for me again and again how I imagine myself to be unhappy if a certain other becomes happy. It's a little coo-coo, but metta's radical scope (metta for all!) exposed some faulty core beliefs.

My Tibetan teacher has said something in the same vein when he has talked about how peaceful deities and their practices are much more necessary these days than wrathful ones. Wrathful deities can bring energy, and powerful compassion, and quick decisive action. But according to him, people can get caught up in ego trips relating to intensity and peak experiences, and sensory stimulation (so much blood! so many flames!). He says that peaceful deities by contrast accomplish the same goals through a different type of intensity: the intensity of unwavering love and compassion for all beings, even for all phenomena, and not as a trip but as simply an essential quality of their own being. The unwavering aspect can be quite daunting as can be the bit about no exceptions. Really thwarts the attempts at wiggling away.

I've never really thought about metta in the spirit of Zen before today. What I mean by metta in the spirit of Zen is the practice of metta without even a goal or agenda for the practice. Practicing metta simply as an expression of who we are in each moment of practice. In this way, all the yanas are united. A Theravadan practice takes on the Zen spirit of no path, no goal, no gain and arrives at what might be conceived of in tantric terms as a sort of purity or dignity. These latter descriptors are without reference and not opposed to impure or undignified, and yet they point to an energetic state being able to relax into the state of things being just as they are.

So my advice is to please practice metta with as much kindness and clarity as you can.

Monday, June 18, 2012

Anathapindikovada Sutta

It's pretty incredible as a bridge between schools of Buddhism both 1) in its essential message and method that it could be said to share with the Heart Sutra, and 2) the end of the narrative (see links) wherein Anathapindika uses his dying words to suggest that there are lay followers who should hear the highest teachings because they can actualize them even without becoming monastics.

Here are some highlights (abridged by me, translation by Thanissaro Bhikkhu):

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Deep Listening II

Here's the audio from this past weekend's meeting of Queer Sangha, where Rev. Do'an and I speak about deep listening.

Enjoy!

Monday, June 11, 2012

Deep Listening

It's been too long, friend. Strange and hard and wonderful things have happened in my life since the last post. I've continued to enjoy the honeymoon period with my love, and consequently I've been working on being the best partner I can be and also thinking about what that means. I've had a bout of my recurrent illness, and I was in the hospital for a week. I've been recovering well, and I'm grateful to have health insurance and a job that gives me sick leave for this sort of thing. My birthday, and my mom's birthday, and mother's day have come and gone. And I recently learned to weave and to make simple backstrap looms.

I haven't had much contact with my Zen teacher lately due to my illness/recovery and circumstances affecting our schedules, and I miss him. He has a wonderful way of balancing the iconoclasm and freshness of Zen with Truths as they are presented in other Buddhist traditions in ways that are not in conflict. For example, I sometimes feel tension between the viewpoint of Zen schools that have stopped even talking about enlightenment or the four noble truths and teachings about liberation as they are presented in other Zen schools and lineages of Buddhism. I can eek out a point of view in which there is no conflict, but he does it with much more ease. I know there are benefits to both ways of looking at things, but easily fall into a mindset that necessitates choosing one approach or the other, whereas he sees them as not different.

Yesterday, my Dharma brother Rev. Lawrence Do'an Grecco and I gave a Dharma talk on deep listening to the Queer Sangha for which we teach. I'm sure he'll throw a link up to the audio in the next few days, so check back. It was a wonderful thing to reflect on. I was inspired to suggest it as a topic by a chapter on listening in Norman Zoketsu Fischer's book Taking our Places; a Buddhist path to truly growing up. I highly recommend this book and Normal Fischer in general.

I'm also looking forward to meeting someone I've been interested in for some time and with whom I seem to share much in common: Barry Magid- psychoanalyst and one of the Dharma-heirs of Charlotte Joko Beck. We're going to get coffee later this week.

I've been taking this time lately to pull back from some commitments and to do some deep listening inwardly and with some nears and dears. I think this may be what this season is about for me. I will try to post more often though

Monday, March 19, 2012

Poppy in the Graveyard; Getting to know Avatamsaka teachings

I have never loved someone the way I love you

I have never seen a smile like yours

And if you grow up to be king, or clown, or pauper

I will say you are my favorite one in town

I have never held a hand so soft and sacred

When I hear you laugh, I know heaven’s key

And when I grow to be a poppy in the graveyard

I will send you all my love upon the breeze

And if the breeze won’t blow your way, I will be the sun

And if the sun won’t shine your way, I will be the rain

And if the rain won’t wash away all your aches and pains

I will find some other way to tell you you’re okay

The Avatamsaka Sutra (Chin. Hua Yen Jing, Eng. "Flower Garland Discourse")is an enormous Mahayana Sutra. One English translation wraps up at well over 1,000 pages. Though it's an Indian work, it had its hayday and largest influence in China in the 600s-800s thanks to adepts like Fazang who were able to plumb and communicate its depths. It describes a cosmology of infinite realms, each interpenetrating and containing the other.

This song by My Brightest Diamond reminded me of the way these teachings were explained to me by my Zen teacher: There is a beautiful sun in the sky. The sun evaporates water below, which forms clouds. The clouds fall as rain. The rain and sun nourishes grass. Cows eat the grass and see with the sunlight. The cows make milk. The farmer collects milk and processes it. He sells it to people who make ice cream. They sell it to a little boy. The little boy eats it on a hot day, and he smiles. His smile contains the sun and all the other factors. His smile IS the sun, and also many other things. The sun is also the little boy and his smile, and grass, and cows, etc.

I have thoughts about how this idea might enable us to live happier lives by perceiving reality in a different way, but before I write a post about it, I'd love to read your comments about what you might take from such an idea.

Monday, March 5, 2012

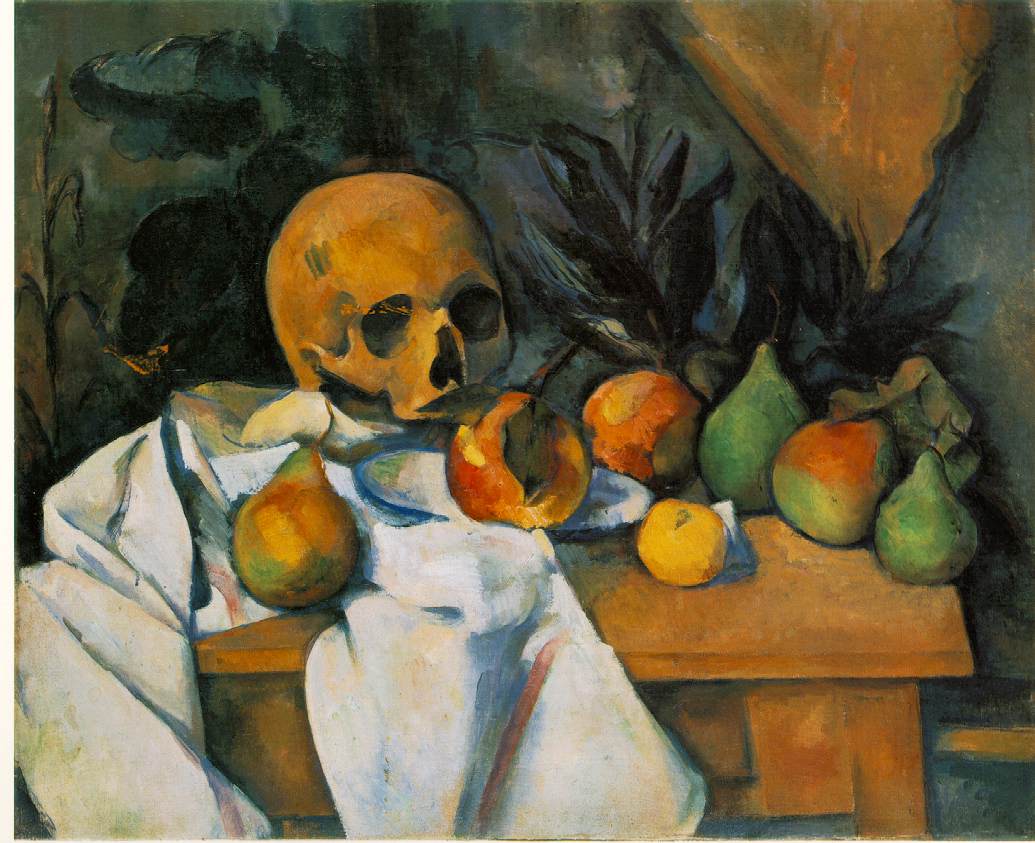

a Question is Posed to a Not-Still Life

One of my favorite ways to make meditation deeper is to observe the interplay of skandhas. From the early Buddhist point of view, these factors are what make up the world and a conventional self. They are divided into two: rupa (form) and nama (for the moment, let's just call this something without form).

A Not-Still Life

A Not-Still LifeNama itself can be broken into feelings (vedana), perceptions (samjna), mental formations (samskara), and consciousness (vijnana). I could go into a much more long-winded explanation of what these things are and how they interact. I want to, but I won't right now. You can check all of these out on wikipedia or other websites. If the self is like a painting, suffice it to say that the skandhas are not like the painting that we normally perceive (a more two-dimensional quasi-cohesive sense of Self), but rather like the actual fruit and flowers the painting was modeled after. Not the still life version of "insert your name here", but a beautiful moving field of objects interacting.

I want to highlight that in Theravada tradition, there are a number of ways of benefiting from being aware of these things at play in one's field of awareness. To my way of thinking, the most important benefits are recognizing that none of these things have some sort of inherent selfhood, although they sometimes work in concert to produce a feeling or sense of Self. Seeing through that illusory sense into these compositional factors can be very liberating. One way of recognizing the not-self nature of them is to notice how they change constantly--appear, disappear, wax, wane, etc. This is one among many marvelous Theravadan techniques to reach liberation from suffering. The suffering that is bound up in a sense of self that loses and wins and hurts and gains and is shamed and gets haircuts, etc.

A Question

In Chinese Chan and Korean Seon (to a lesser extent in Japanese Zen), there exists a practice of sitting with and concentrating on a question called in Chinese Huatou (Kor. hwadu, Jp. wato) . It is like a koan, in that it produces an awakening experience and shift of perspective. Unlike a koan, it may not produce an answer that is communicated even if it does produce the enlightening experience. Zen Master Seung Sahn liked an unusual huatou that comes prefab with its own answer:

What is this?I have to admit, when I heard my Zen teacher or the writings of his predecessor talk about holding the Question and its answer, I thought it was pretty weak. After all, I've spent over a decade looking pretty closely at different objects of meditation. I think I've even done it in a way that isn't too heady or conceptual (okay, maybe not at first). While I'm not some great yogi, I at least trust my ability to pay close attention to what I can perceive--not just wave it all away with a thought of Don't Know.

Don't know.

I even sometimes catch whiffs of my own arrogance when I think of other people using this huatou. At first it seemed not only anti-intellectual (which is fine by me) but actually anti-curious (which is not fine by me, or at least seems to be the most unskillful way to practice Buddhism). I mean, somebody could just mumble this all day like a mantra and not even scratch the surface of paying attention to what's in front of them. I thought of it as a way of cutting thoughts not through actual experience of cutting through to the vividness underneath, but rather as a way of swallowing somebody else's realization. "Don't know" doesn't mean anything unless you actually wonder "what this is"!

I noticed a change in my haughtiness when I simply adjusted the microscope. No longer was it a two-phrase mumble, but it was a way of sitting with the unfathomability of subjectivity. And this shift happened when I applied the question to smaller "internal" phenomena: the skandhas

What is purple? Don't know. But don't particularly care either. However, what is unpleasant (vedana)? Or eye-consciousness (vijnana)? Or aversion (nivarana)? That don't know is interesting. The experience of looking at one of those phenomena dead on and wondering what it is from a nonconceptual point of view is very, very interesting. Interesting isn't the right word. Sounds academic. I mean enlivening, freeing.

Maybe all this means is that I have judgment in the mind and I'm lacking a penchant for applying this huatou to mental formations, but at least I now have a sense for how the huatou really works. I feel very curious and energized by the application of this huatou to the ever-changing constellation of mental factors.

And if you like purple, enjoy don't know purple!

Thursday, March 1, 2012

...with as much clarity and kindness as you can.

There have been a number of things on my mind lately, the above among them, that have served to disperse my concentration: a difficult client, the possibility of dating someone new, financial stress, travel plans, teaching, illness, visitors.

I want to share an approach to dealing with these types of daily life concerns that has served me enormously: formal metta practice. I hereby inaugurate my next installment of Don't Make Anything... because this practice really helps to do that.

I think the practice whose effects have been most observable for me has been formal (and I guess informal) metta meditation practice. Metta is a Pali word that means something like loving-friendliness.

The Buddha Shakyamuni explicitly taught many metta practices that are recorded in the suttas/sutras. And there are many ways of practicing. Here in the west, the most common is probably the mental repetition of metta verses. The traditional formulation contains one verse each on safety, mental happiness, physical wellness, and ease in life circumstances. One example is Sylvia Boorstein's wording:

May I feel safe.

May I feel happy.

May I feel strong.

May I live with ease.

These are repeated as a way of blessing oneself or others. In traditional practice, one devotes a block of time (one session or weeks of sessions) directing metta first to oneself. Then the practitioner moves on to friends, relatives, or benefactors who easily evoke feelings of warmth. Then neutral people--these are people we pass in the streets or people we might otherwise ignore. Then difficult people. Then all beings.

You don't have to strive to develop love and warmth while you're practicing. The phrases will get under the skin regardless. I just try to stay concentrated on the verses themselves with as much clarity and kindness as I can. Even if it's not much at a particular moment.

I practice this in an unusual way-- I only practice formally on the cushion for myself, whereas I practice off the cushion for all the other classes of beings. I started this way several years ago in order to improve my relationship with myself. Guess what? It worked. A major effect was that I developed a sort of inner voice that I didn't quite internalize when I was growing up. It's okay. Do your best. It'll pass. You're only human. You did it! And so on. It wasn't my intention to develop these thoughts specifically; it just happened.

Another spillover effect was that my kindness towards myself extended to others without much effort. Oh, she's just like me. Look at him, he's hurting. I do that [annoying thing] too sometimes.

I rarely practice formal metta for others on the cushion. I do it on the street (may he find nourishment and be happy), on the train (may her life become peaceful), at work (may they be strong). These thoughts might superficially appear dualistic (subject-object), but the mental texture of these thoughts is very light and slippery. They don't make a storyline at all. It's like writing with your finger on the surface of water.

I also like to let my mind wander as I'm going to sleep and direct metta to whomever comes to mind. It's very de-stressing, and I feel intimate with others in a way that feels very light.

When I'm afflicted by the circumstances I mentioned at the beginning of the post, I try to check in with myself with some metta. When I'm sick, I think: may I be well. When I'm being pulled in all directions I think: may I live with ease. I repeat them over and over but with clarity so that I'm aware of the meaning of my aspiration.

For anyone who might like inspiration in this practice, I recommend Sharon Salzberg's Loving-kindness; the Revolutionary Art of Happiness, the books and podcasts of Sylvia Boorstein or Arinna Weisman, or the wonderful biography of 20th century enlightened master Dipa Ma.

Thursday, February 23, 2012

One method of cutting the concepts & Relating to Pain

My friend Emily is staying with me, and this morning I awoke to find her grumbling. She asked if I could surgically remove her uterus. Several hours and many yards of gauze later... just kidding. She was hurting!

I would have resisted my urge to mansplain something to her about pain, but as I was heating a hot water bottle for her and she curled up in a ball, we got into a discussion about different ways of relating to pain. I'll keep the discussion private, but here's one approach to using meditation to change your relationship with unpleasant experiences.

I've practiced vipassana meditation regularly for several years, and one of the four objects of vipassana listed in the Satipatthana Sutta is vedana. Vedana is often translated as "feelings", but in this context it does not mean emotions. Emotions are much more complex. The psychology term "hedonic tone" or a more colloquial phrase like "feeling tone" might be more useful. According to the Buddha and modern neuroscience (if you need me to dig up a reference, contact me), most perceptions are almost immediately followed by a reactive tone in the mind: pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral (neither wholly pleasant nor wholly unpleasant). I don't want to reduce this to a brain function alone, but one of the jobs of the amygdala is to immediately make a snap judgment about stimuli coming through the sense organs in order to determine safety.

Practicing vedana as the object of vipassana (this process is called vedananupassana) means simply noting the tones that arise in response to stimuli in the body or the environment. I practiced this as my main form of meditation for several months a few years ago, and its effects have made some lasting changes in how I relate to my world. At first it seemed like the feeling came with the stimulus, but after a while, I noticed that there was a tiny, tiny gap between the sensation of a comfortable breath and the subtle rush of pleasure that came after it.

This came in handy during a retreat, when I was experiencing some wicked back pain between my shoulders. I hunkered down and paid deep attention to the gap between the sensation and the tone that followed almost immediately. As I attempted to zoom in, I could actually beat the feeling tone to the punch. When I was able to do that successfully, the sensation felt electric, and I could experience it change in mental texture and intensity. The intense sensations almost felt like a sort of rapture. Not pleasant but blissful. I suspect these were flickers of piti (Pali, "rapture") arising from deep concentration.

Explicitly noticing how the mind categorizes almost everything it's aware of as being pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral generates a deep familiarity with those categories. This benefited me in a few ways that I noticed viscerally:

-The mind mostly ignores or quickly moves on from things that are neutral- neither wholly pleasant, nor wholly unpleasant. But upon examination, some things are worth paying attention to even if they don't create a pleasant or unpleasant feeling.

-When unpleasant things happened, I was able without almost any effort to recognize that I deal with unpleasant stuff all the time. One more unpleasant thing is no big deal. In fact, unpleasant isn't really all that different than pleasant. They're almost like different colors. One is purple, the other blue. Purple is not blue, but they're really just two versions of the same thing. Unpleasant is no problem. Conversely, pleasant is also no big deal. The mindstate produced by being somewhat desensitized to pleasant and unpleasant is equanimity, but a very restful, alert, and content equanimity. It's all ok.

-When I was experiencing something as unpleasant in my everyday life, something changed when I would say quietly to myself, "well, this is unpleasant." It was as if the negativity of the feeling tone wasn't as strong as the pleasure of being able to catch and recognize that response in the mind. It created a sort of perspective, a step back, some breathing room, and enough space to see the situation and my mind's response to it with a little more clarity and a sense of humor.

I'm a psychotherapist by trade, and I can remember having a session a couple years ago that went pretty badly. After the session ended, and I was sitting at my desk, I threw my head back and exhaled, "well, that was unpleasant!" It was as if I had put the whole thing in the unpleasant bin, where I knew just what to do with it. No story lines necessary. No heroes or villains or agendas.

Just to drive home the point: with this kind of meditation, no effort is made to judge the phenomena that are noticed. That's just judging, not meditation. The practice is to find the tone (sometimes almost a bodily feeling) that comes up along with experiences that arise inside or outside the body.

Happy practicing!

Monday, February 20, 2012

Wake-up Sermon says Don't Make Anything!

When you understand, reality depends on you. When you don't understand, you depend on reality. When reality depends on you, that which isn't real becomes real. When you depend on reality, that which is real becomes false.... everything becomes false. When reality depends on you, everything is true. -Bodhidharma, the Wake-up Sermon

What the crap does that mean?! Well, I don't like to look at these words as a logic proof. After we are done playing with ideas, we each must bathe or cook or sleep or make love or pay our bills if we can. My experience is that if we are to gain anything from being on path with teachings like these, we must apply them to the every day. Otherwise, we're just making new schemas. I think part of what Bodhidharma is saying in his quote is that when the mind is in balance, we can be in relationship to these daily activities without getting caught up in the idea of them.

There are many ways to understand paying a bill: writing names and numbers on a small piece of paper that gets mailed; acting to prevent a future action (losing electricity); maintaining an agreement, etc. These are all just ideas, and some are sometimes more helpful than others. Still, when we have hope and fear around these ideas, we're living in the future based on our perceptions of the past. This is not a great way to rest the mind. Neither is avoiding action for the same reasons.

Sylvia Boorstein has a saying that comes to my mind often (if inaccurately). It's something like, "when the mind is at peace, one's behavior becomes impeccable." I think that's true. And I think it's worth saying that impeccable has to be free from any idea of right or wrong, or even of impeccability. I never knew him, but I think Dae Soensanim (Zen Master Seung Sahn) might have expressed this idea by saying something like, "Mind is clear, behavior is No Problem!"

I highly recommend imagining what it would be like if you were an actor hired to play (insert your own name) in a "reality" TV show. You're just being you, responding to what comes next in the script. Does your perspective shift?

Tuesday, February 14, 2012

longer introduction

Do-Myong Sunim lives in Brooklyn and is a licensed clinical social worker in the state of New York, where he specializes in working with young people who have experienced trauma. He is especially interested in the integration of Attachment Theory and recent advances in affective neuroscience into psychotherapy and other brain/body-based approaches to healing. He also partners with organizations to do social justice work in various capacities, particularly for and with queer youth of color. In his sparse free time, Rev. Do-Myong Sunim can be found digging away in the garden or hovering over a cup of tea.