(disclaimer: this post is less of a how-to than most of my others.)

One of my favorite ways to make meditation deeper is to observe the interplay of

skandhas. From the early Buddhist point of view, these factors are what make up the world and a conventional self. They are divided into two:

rupa (form) and

nama (for the moment, let's just call this something without form).

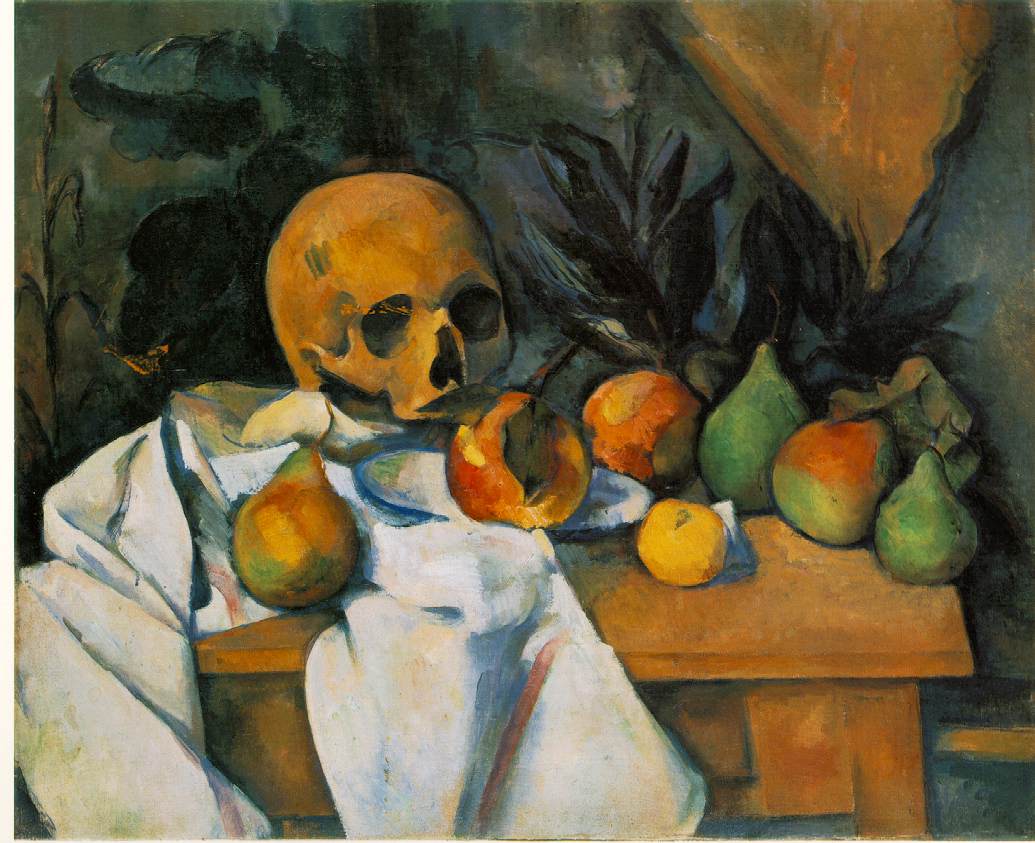

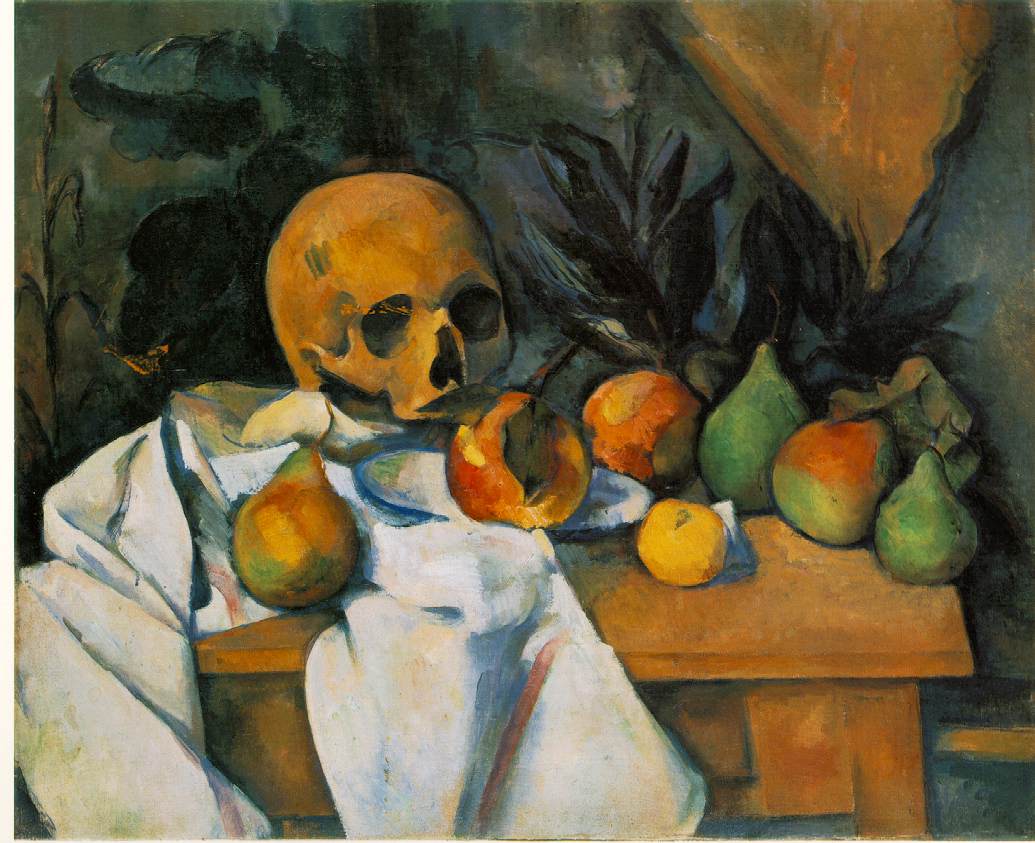

A Not-Still Life

A Not-Still LifeNama itself can be broken into feelings (vedana), perceptions (samjna), mental formations (samskara), and consciousness (vijnana). I could go into a much more long-winded explanation of what these things are and how they interact. I want to, but I won't right now. You can check all of these out on wikipedia or other websites. If the self is like a painting, suffice it to say that the skandhas are not like the painting that we normally perceive (a more two-dimensional quasi-cohesive sense of Self), but rather like the actual fruit and flowers the painting was modeled after. Not the still life version of "insert your name here", but a beautiful moving field of objects interacting.

I want to highlight that in Theravada tradition, there are a number of ways of benefiting from being aware of these things at play in one's field of awareness. To my way of thinking, the most important benefits are recognizing that none of these things have some sort of inherent selfhood, although they sometimes work in concert to produce a feeling or sense of Self. Seeing through that illusory sense into these compositional factors can be very liberating. One way of recognizing the not-self nature of them is to notice how they change constantly--appear, disappear, wax, wane, etc. This is one among many marvelous Theravadan techniques to reach liberation from suffering. The suffering that is bound up in a sense of self that loses and wins and hurts and gains and is shamed and gets haircuts, etc.

A QuestionIn Chinese Chan and Korean Seon (to a lesser extent in Japanese Zen), there exists a practice of sitting with and concentrating on a question called in Chinese

Huatou (Kor.

hwadu, Jp.

wato) . It is like a koan, in that it produces an awakening experience and shift of perspective. Unlike a koan, it may not produce an answer that is communicated even if it does produce the enlightening experience. Zen Master Seung Sahn liked an unusual huatou that comes prefab with its own answer:

What is this?

Don't know.

I have to admit, when I heard my Zen teacher or the writings of his predecessor talk about holding the Question and its answer, I thought it was pretty weak. After all, I've spent over a decade looking pretty closely at different objects of meditation. I think I've even done it in a way that isn't too heady or conceptual (

okay, maybe not at first). While I'm not some great yogi, I at least trust my ability to pay close attention to what I can perceive--not just wave it all away with a thought of Don't Know.

I even sometimes catch whiffs of my own arrogance when I think of other people using this huatou. At first it seemed not only anti-intellectual (which is fine by me) but actually anti-curious (which is not fine by me, or at least seems to be the most unskillful way to practice Buddhism). I mean, somebody could just mumble this all day like a mantra and not even scratch the surface of paying attention to what's in front of them. I thought of it as a way of cutting thoughts

not through actual experience of cutting through to the vividness underneath, but rather as a way of swallowing somebody else's realization. "Don't know" doesn't mean anything unless you actually wonder "what this is"!

I noticed a change in my haughtiness when I simply adjusted the microscope. No longer was it a two-phrase mumble, but it was a way of sitting with the unfathomability of subjectivity. And this shift happened when I applied the question to smaller "internal" phenomena: the skandhas

What is purple? Don't know. But don't particularly care either. However, what is unpleasant (vedana)? Or eye-consciousness (vijnana)? Or aversion (nivarana)?

That don't know is interesting. The experience of looking at one of those phenomena dead on and wondering what it is from a nonconceptual point of view is very, very interesting. Interesting isn't the right word. Sounds academic. I mean

enlivening, freeing.

Maybe all this means is that I have judgment in the mind and I'm lacking a penchant for applying this huatou to mental formations, but at least I now have a sense for how the huatou really works. I feel very curious and energized by the application of this huatou to the ever-changing constellation of mental factors.

And if you like purple, enjoy don't know purple!